The Phaethon Myth – Hubris & Catastrophe

The story of Phaethon is one of the more notable tales within Greek mythology; a collection of myths and teachings integral to the ancient Greeks. Fantastic legends that encompassed their gods and heroes, the nature of the world, and the origin and significance of their culture and rituals.

Phaethon’s tale is believed to have first been told around 700 BC as part of the oral storytelling tradition of the Greeks, well before the advent of written literature. The two most important surviving texts that give the fullest account of the Phaethon myth, compiled far later, are as follows:

- The "Metamorphoses." A narrative poem in 15 books by the Roman poet Ovid written in Latin around 8 AD.

- The "Library." A compendium of myths and heroic legends arranged in three books by an unknown author known as Pseudo-Apollodorus.

The story revolves around the central character Phaethon, the son of the sun god Helios, and his tragic attempt to drive his father's ‘chariot of light’ for a single day. On its face a dramatic story of hubris and ambition, but correctly decoded, an explanation for various natural phenomena – especially of the destructive variety e.g. the scorching heat of the sun and the creation of deserts.

It is a story that has been retold and referenced in various forms of art and literature throughout history, highlighting its enduring appeal and cultural significance.

The Story of Phaethon

The tale of Phaethon commences with the young man questioning his mother Clymene about the identity of his father. Upon learning that his father is Helios, the god of the sun, Phaethon embarks on a journey to the far east, where the palace of the sun god resides. An overwhelming desire to meet his father, and even gain acceptance of his status.

Upon reaching the magnificent palace and entering within, Phaethon immediately finds himself in the presence of the sun god, along with his array of attendants:

The Sun, dressed in a purple robe, was sitting on a throne bright with shining emeralds. On his right hand and on his left stood Day, Month, Year, the Generations and the Hours, all ranged at equal intervals. Young Spring was there, his head encircled with a flowery garland, and Summer, lightly clad, crowned with a wreath of corn ears; Autumn too, stained purple with treading out the vintage, and icy Winter, with white and shaggy locks.

From Ovid’s Metamorphoses

Initially dazzled by the brilliant scene before him, only after gathering his courage is Phaethon able to approach Helios. Surprised by his son's boldness but pleased by it too, Helios welcomes Phaethon, acknowledging him as his son. To prove his love and paternal linkage, Helios swears a solemn oath by the River Styx - an unbreakable vow according to the customs of the gods. A promise to grant Phaethon whatever he wishes.

Seizing the opportunity, Phaethon requests to be allowed to drive his father's sun chariot for a day. Immediately realising the danger inherent to his son's wish – which he had not anticipated – Helios tries to dissuade Phaethon, telling him of the immense difficulties and perils involved in controlling the powerful horses tethered to his chariot. Despite his father's warnings however, Phaethon is adamant about his wish. An overriding desire to prove his prowess and heroism; he insists on driving the sun chariot.

Bound by his oath despite his grave concerns, Helios finally gives in to his son's unwavering demand, reluctantly agreeing to let Phaethon drive the chariot of light for a single day.

Phaethon Commands the Sun Chariot

As the day begins at the break of dawn, Phaethon’s initial skyward ascent in the sun chariot is all excitement and triumph. Soon sensing that their driver is not their regular master however, the four fiery horses drawing the chariot become restless and uncontrollable. Inexperienced and unable to command them as they become agitated, Phaethon struggles to keep his grip on the reins and prevent the chariot from veering off course.

As he progresses in his journey whilst fighting to steer a steady path, yet further troubles beset him, adding to his fears:

He now perceived the monstrous beasts of huge size, which lay scattered over the spangled face of heaven. There is a certain place where the scorpion stretches out his pincers in two hollow arcs, and with his tail and curving claws outspread on either side sprawls over two signs of the zodiac. When the boy saw him, exuding his baneful poison, and menacing him with his curved sting, he was so completely unnerved and numb with fear that he dropped the reins. They fell from his hands, and lay loose on the horses’ backs. At once, the team galloped away, out of their course.

From Ovid’s Metamorphoses

It was at this point that Phaethon lost all control over the sun chariot. The horses then running rampant without a master, the chariot began to deviate wildly from its proper course, causing all manner of chaos.

At first it soared too high, heating up the stars in the high heavens. And then dangerously low, scorching the earth’s fields and forests, creating deserts and drying up rivers. The people around the world also suffered under the extreme burning heat of the sun. With Phaethon no longer master of the chariot but merely a passenger along for the ride, both the heavens and the earth were thrown into upheaval.

Phaethon’s Fall

Seeing the devastation, the earth goddess Gaia cried out to Zeus – the father of all the gods – for his assistance. Recognizing the need to intervene to prevent further disaster, Zeus took up his mighty thunderbolt, and with careful aim hurled it directly at Phaethon, knocking him from the chariot with a lethal deathblow. A devastating impact which broke the chariot apart and released the horses from the yoke:

The fragments of the wrecked car were scattered far and wide. But Phaethon, with flames searing his glowing locks, was flung headlong, and went hurtling down through the air, leaving a long trail behind: just as sometimes a star, though it does not really fall, could yet be thought to fall from the clear sky. Far from his native land, in a distant part of the world, the great river Eridanus received him, and bathed his charred features.

From Ovid’s Metamorphoses

With Phaethon's ill-fated journey brought to an end, the world was spared further destruction.

Mourning Phaethon’s Death

Buried by the river nymphs of Eridanus, Phaethon’s death was deeply mourned by his sisters, the Heliades, who were transformed into poplar trees as they shed amber tears at his passing. Even Helios too was struck by immense grief. The loss of his son having quite an effect upon him:

Phaethon’s unhappy Father, sick with sorrow, had veiled his face, and hidden it from sight. If we can believe it, they say that one day passed without the appearance of the Sun: the burning fires gave light, so that the disaster served some useful purpose.

From Ovid’s Metamorphoses

Deeply disturbed by the death of Phaethon and furious at Zeus for his part in it, Helios was quite intransigent about resuming his regular duty of giving light to the world. Only after much cajoling from the other gods did he finally relent and resume his task, rounding up the horses once more to command the chariot of light.

Phaethon’s

Death: Encoding A Destructive Celestial Alignment

One may read many things into the story of Phaethon. That it was devised as a cautionary tale against over ambition, or a warning not to dismiss the advice of those with greater wisdom. In essence, a ‘life lesson.’ Such considerations are however merely surface level; concerned solely with the drama of the tale itself.

In point of fact, the story of Phaethon was very carefully constructed to encode the key elements of a very specific planetary configuration. One that involved multiple conjunctions occurring simultaneously on a very precise date in history. In this regard, the key date in question was well noted in the classic work by Immanuel Velikovsky, Worlds in Collision, published in 1950. A date associated with the destruction of the army of Sennacherib as he lay siege to Jerusalem in the seventh century BC.

Within the Bible, this event is described in the book of Isaiah, wherein Yahweh, the God of the Israelites, destroys the army of Sennacherib with a blast from heaven, wiping out 185000 men at a stroke. According to Velikovsky, this was not the act of a wilful god however, but rather a very real celestial disturbance, wherein fire did indeed rain down upon the Earth: An entirely natural event.

The relevant passage from worlds in collision is as follows:

It was apparently some cosmic cause that was responsible for the sudden destruction of the army of Sennacherib and brought about the perturbation in the rotating movement of the earth.

First, a more exact date for the night of the annihilation of Sennacherib's army should be established. From modern research we know that it was in the year -687 (less probably in the year -686). The Talmud and Midrash give another valuable clue: the destruction occurred during the first night of Passover. The giant host was destroyed when the people began to sing the Hallel prayer of the Passover service. 1 Passover was observed about the time of the vernal equinox. 2

In the book of Edouard Biot, Catalogue général des étoiles filantes et des autres météores observés en Chine après le VIIe siècle avant J.C., 3 the register begins with this statement:

"The year 687 B.C., in the summer, in the fourth moon, in the day sin mao (23rd of March) during the night, the fixed stars did not appear, though the night was clear [cloudless]. In the middle of the night stars fell like a rain."

The date, 23rd of March, is Biot's calculation. The statement is based on old Chinese sources ascribed to Confucius. In another translation of the text, by Remusat, 4 the last part of the passage is rendered as follows: "Though the night was clear, a star fell in the form of rain" ("il tomba une étoile en forme de pluie").

The annals of the Bamboo Books obviously refer to the same event when they inform us that in the tenth year of the Emperor Kwei (the seventeenth emperor of the Dynasty Yu, or the eighteenth monarch since Yahou) "the five planets went out of their courses. In the night, stars fell like rain. The earth shook." 5 The words in the annals, "in the night, stars fell like rain," are the same as in the record of Confucius dealing with the cosmic event on the 23rd of March, 687 BC.

Worlds in Collision (1950), Immanuel Velikovsky

The Day Of Disaster: 23rd of March, 687 BC

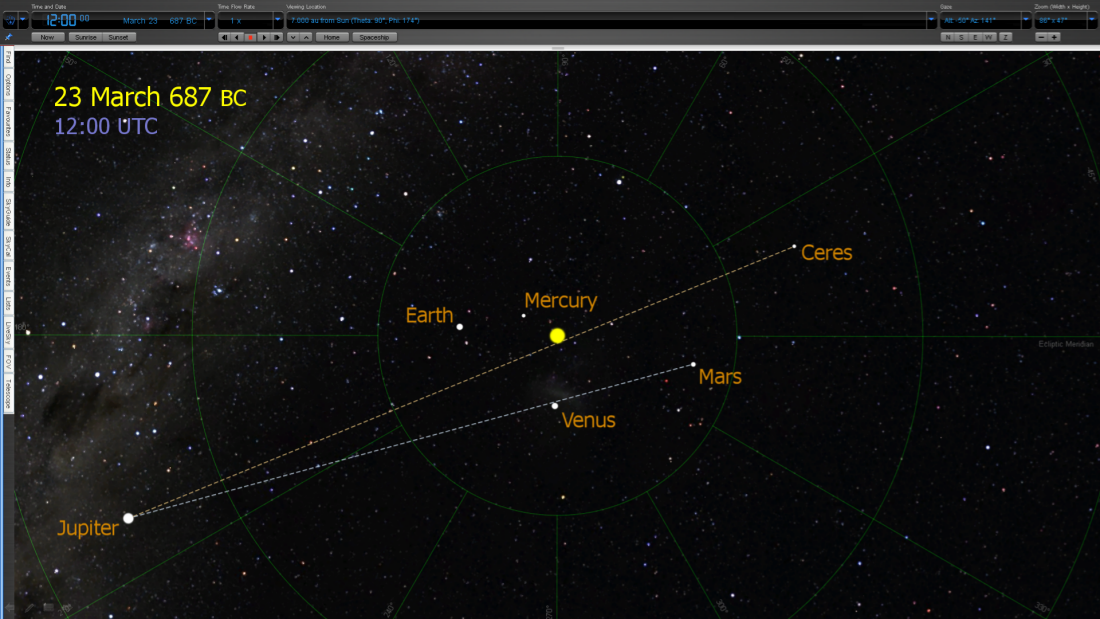

With a precise date identified, one is able to view the solar system with advanced astronomy software to reveal an astounding celestial configuration. Two alignments occurring simultaneously:

Jupiter, the Sun and Ceres, along with Jupiter, Venus and Mars (NB; For an important note on modelling the orbit of Ceres, see note [1] in the Notes section at the bottom of this article):

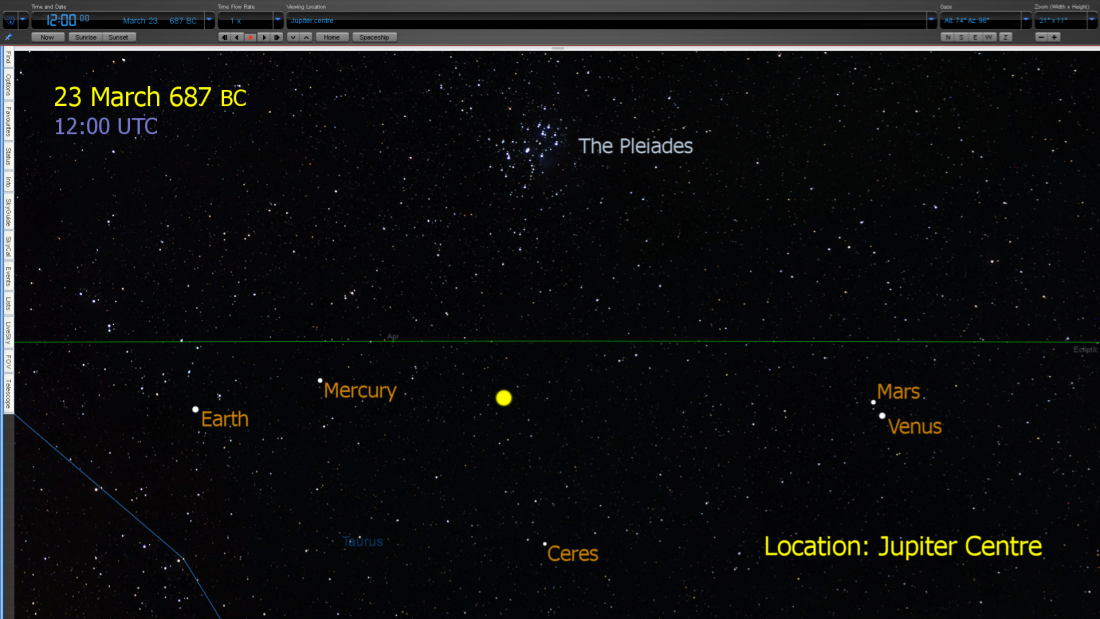

Further to this, when looking down the line of the two conjunctions from the perspective of Jupiter, once more there is a Pleiades connection. The Pleiades star group being aligned with both Ceres and the Sun:

It is the contention here then that this celestial pattern was directly responsible for triggering various exotic destructive effects within the heavens, including significant earthbound devastation.

Examining the cited passage from Velikovsky, there is the hint that the Earth suffered a general physical agitation i.e. intense global seismic activity, along with a temporary disruption to the Earth’s axial rotation. This latter in particular being responsible for the stars ‘moving out of their positions,’ relative to an observer upon the ground.

One may also suggest that the reference to ‘a star falling in the form of rain,’ directly applies to the dwarf planet Ceres, as aligned with the Sun and Jupiter, along with the Pleiades. An alignment that resulted in Ceres developing a cometary tail.

Phaethon: Mythological Confirmation

In studying the noted configuration upon the date in question: 23 March, 687 BC, the crucial point to note is that this very pattern was the foundational basis for the construction of the story of Phaethon.

As per Greek mythology, it is well known that the planet Jupiter represents the god Zeus. Further to this though, the dwarf planet Ceres within the asteroid belt directly represents/embodies Phaethon.

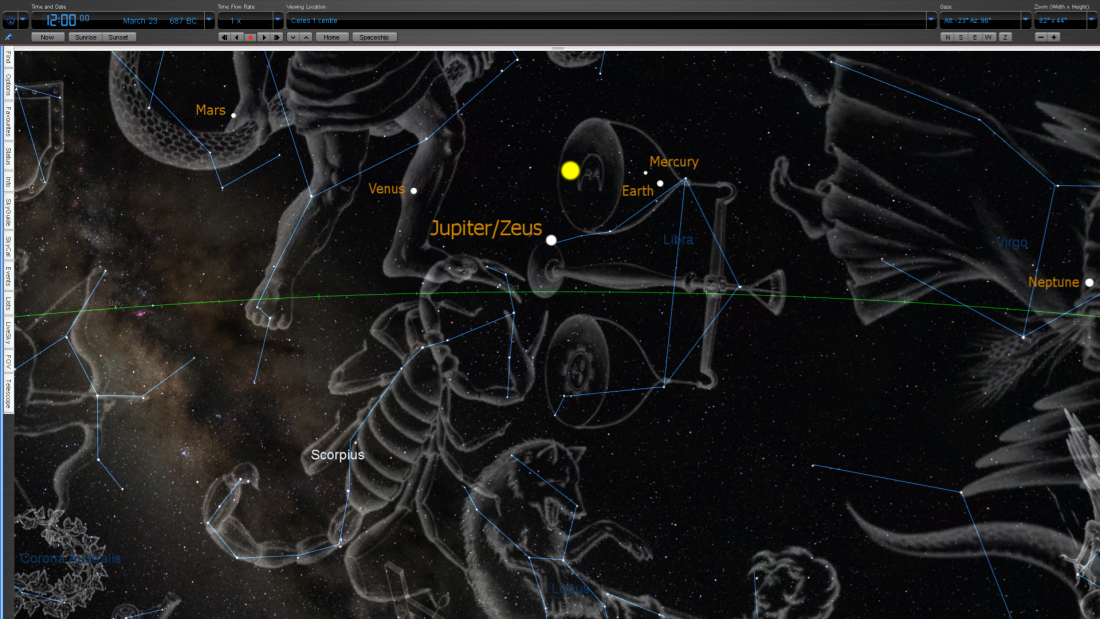

Confirmation of this is to be had when one studies very carefully the background constellations that are also part of the noted alignment: Jupiter, the Sun and Ceres. Firstly, from the perspective of Ceres (below), looking towards the sun and Jupiter, with the background constellations present, one can see Scorpius. Specifically, the pincers of the Scorpion close to Jupiter.

In the story of Phaethon, as related by Ovid, the precise point at which Phaethon loses all control of the chariot of light is when he is directly confronted by ‘the pincers of the Scorpion,’ as detailed:

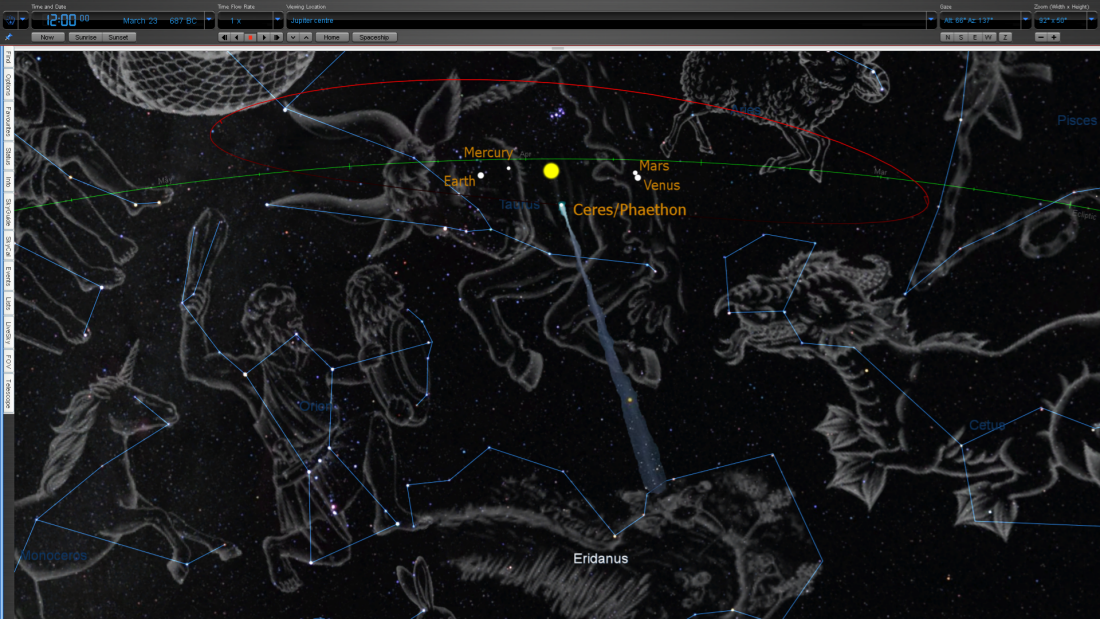

In addition to the above, in switching to the centre of Jupiter and looking towards the sun and Ceres, one can see yet another constellation of note. In this case the Great River Eridanus. To be sure, when any comet moves around the Sun, its tail always points away from the sun, no matter the comet's direction of travel. Given this, the cometary tail extending away from Ceres/Phaethon, as viewed from the perspective of Jupiter, would indeed directly ‘fall’ into the constellation Eridanus:

All of the key elements confirm that the celestial pattern present upon 23 March 687 BC was the basis for the construction of the Phaethon myth. For their part though, the Jews of the Bible recognised the exact same event as being that which destroyed the army of Sennacherib.

Foreknowledge of disaster

There would appear to be very intriguing evidence that somebody knew in advance the precise date of the 687 BC disaster, and set in motion a calendar to target it from the time of the Exodus alignment (1457 BC). This is revealed somewhat indirectly by a certain reference in the Bible. A brief remark that is noted by Velikovsky himself.

Several years ago, as part of a slideshow presentation examining Velikovsky’s work, a group of researchers [2] produced a slide with the following bullet points, one of which is highlighted (here) in red:

Now as given in a previous article, the precise date of the Exodus alignment was 28 March 1457 BC. Here then, one may combine this fact with the above noted reference to the third day following the third new Moon after their [The Jews’] departure [i.e. The Exodus].

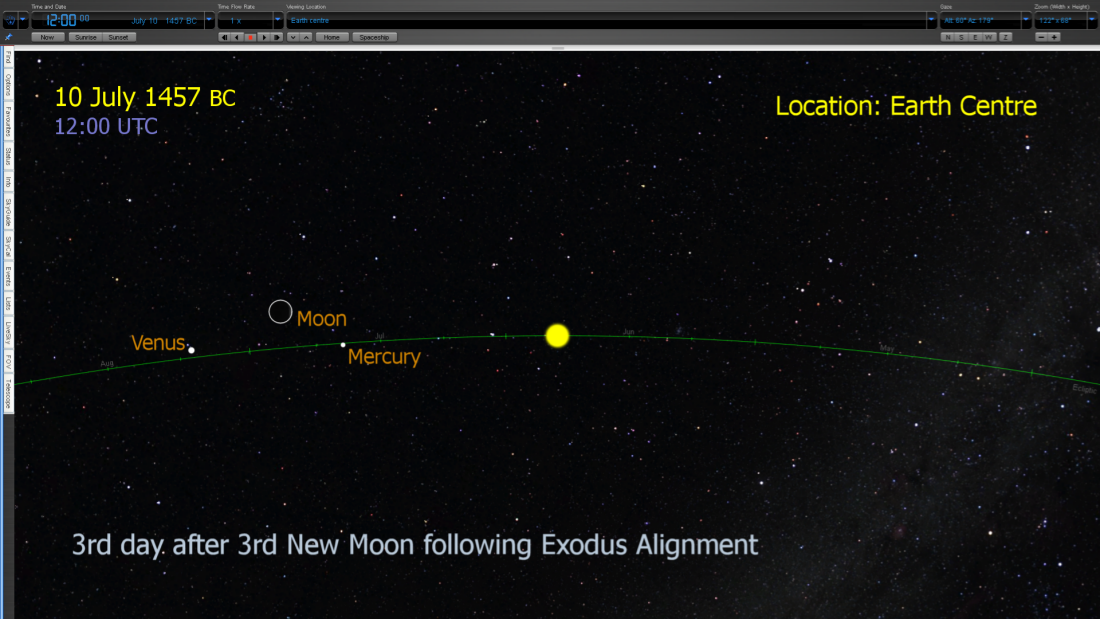

Consequently, the date in question is easily deduced. The following image (below) depicting the event from the viewpoint of the Earth; the position of the moon just to the left of the Sun:

Above: 3rd day following 3rd New moon after The Exodus: 10 July 1457 BC

The significance of this date would not have been lost upon those with the appropriate esoteric knowledge at the time. This being the perfect moment for setting in motion a special calendar system, once more based upon the 819 day cycle. Now the count did not begin immediately upon this date, but rather the date in question was the starting point for a special initial adjustment, before the main count commenced.

Remarkably, the whole mathematical system appears to have been based upon a series of clever mnemonics. Specifically, multiples of a series of ‘foundational’ numbers.

Starting out from 10 July 1457 BC, the first calendar operation was to count exactly 216 days. This figure being the number six multiplied by itself three times: 6 × 6 × 6 = 216:

10 July 1457 BC + 216 days = 11 February 1456 BC

Following this, one begins to count cycles of 819 days. Specifically, 343 such cycles. This figure being the number seven multiplied by itself three times: 7 × 7 × 7 = 343:

11 February 1456 BC + (343 × 819) = 23 March 687 BC

The targeting is dead-on, exactly matching the date of the Phaethon/Sennacherib event; undeniably suggestive of the fact that such a calendar system was in operation at the time. That somebody was fully aware of the significance of the planetary alignments that would occur on 23 March 687 BC.

Additional Crucial Connections

As brilliant as the above mathematical associations are, there are two other points to note, which truly take things to the next level.

1) Targeting the ‘Core Alignment’

When one is tracking time with a special calendar in order to synchronise it with a destructive alignment, it is usually the case that when the alignment is achieved, the calendar needs to be shut down; to be resumed only following some sort of special adjustment, as would target yet another alignment.

Now this indeed is true in most cases. In some instances however, it is entirely proper to keep a calendar going upon reaching a special alignment, if quite naturally, it will go on to connect up to a second alignment of significance, without further alteration. With regard to the 687 BC alignment, this is one such example.

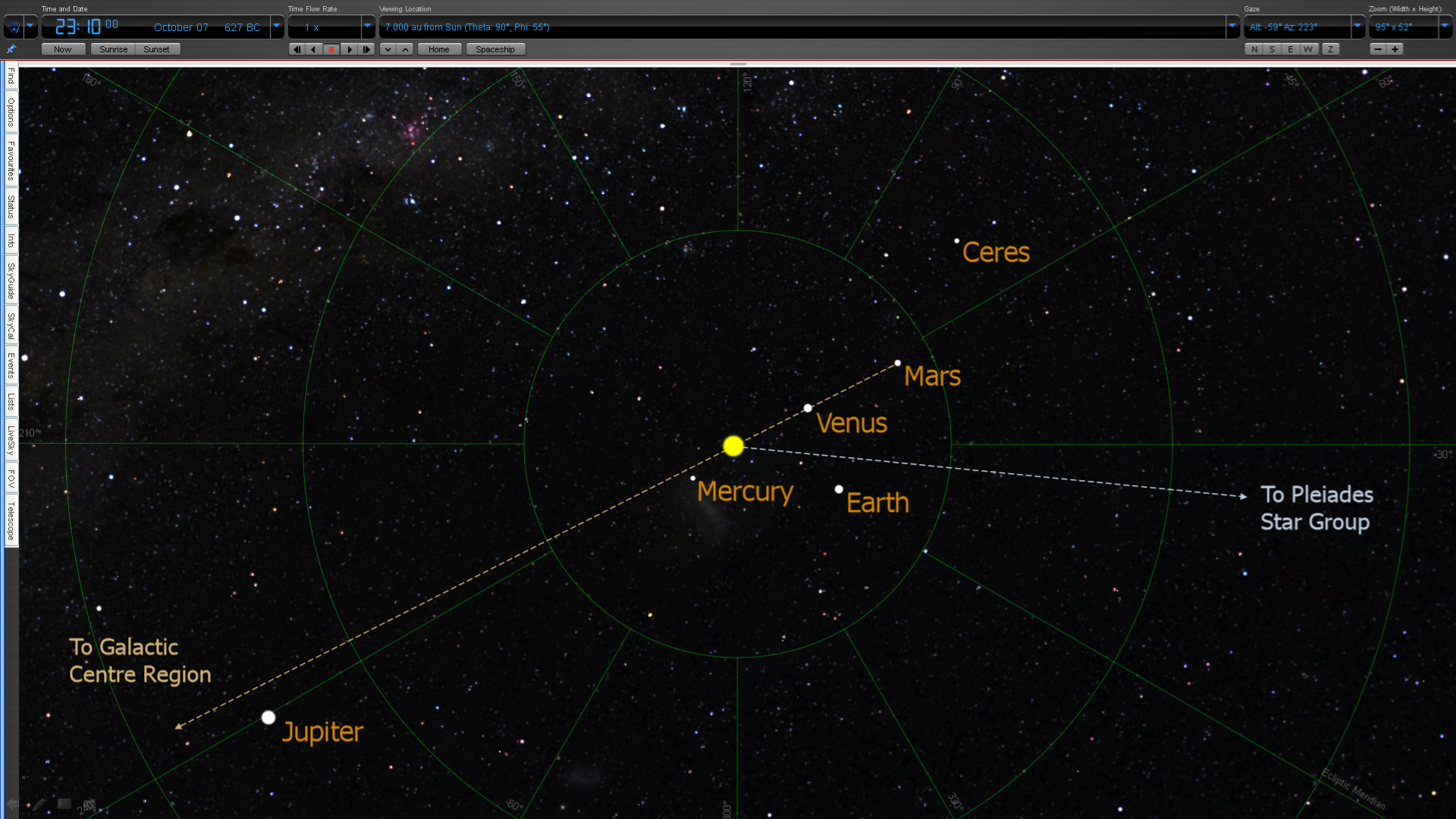

As per the above mathematics, after counting 343 cycles of 819 days to synchronise with the 23 March, 687 BC date, the 819 day calendar does not stop. The correct thing to do is to keep it going without any pause. Specifically, to count an additional 27 cycles of 819 days. In doing so one targets a very special date, as noted elsewhere. That being the date whereupon the ‘core alignment’ is achieved, involving the twin Galactic alignment / Earth-Pleiades conjunctions:

23 March 687 BC + (27 × 819) = 07 October 627 BC

Following the 1970 BC alignment, here then (above) the next instance of the very same alignment is targeted, in 627 BC. This being an alternate method to arrive at the date of the alignment, entirely separate from the mechanics of the Long Count/Calendar Round System of the Maya, which employed an entirely different series of operations.

2) Targeting the Bronze Age Collapse Alignment

Although the Bible, in discussing the siege of Jerusalem by Sennacherib, is indeed discussing a real historical event, one should note that the author of the critical passage in the book of Isaiah, in referring to the size of Sennacherib’s army, is using a ‘fake number.’ That being 185000 men. This was not the true size of his army at all. To be sure, this number was very carefully chosen by the author not to give a simple statement of fact i.e. the size of an army, but rather to encode an element of esoteric knowledge.

Specifically, the means by which one can target a previous destructive alignment, deep into the past. In this case the alignment associated with the Bronze Age Collapse.

The 185000 figure does not represent the number of men in Sennacherib’s army, but rather a number of days that must be counted backwards from the precise date of the 687 BC alignment. This achieves the following:

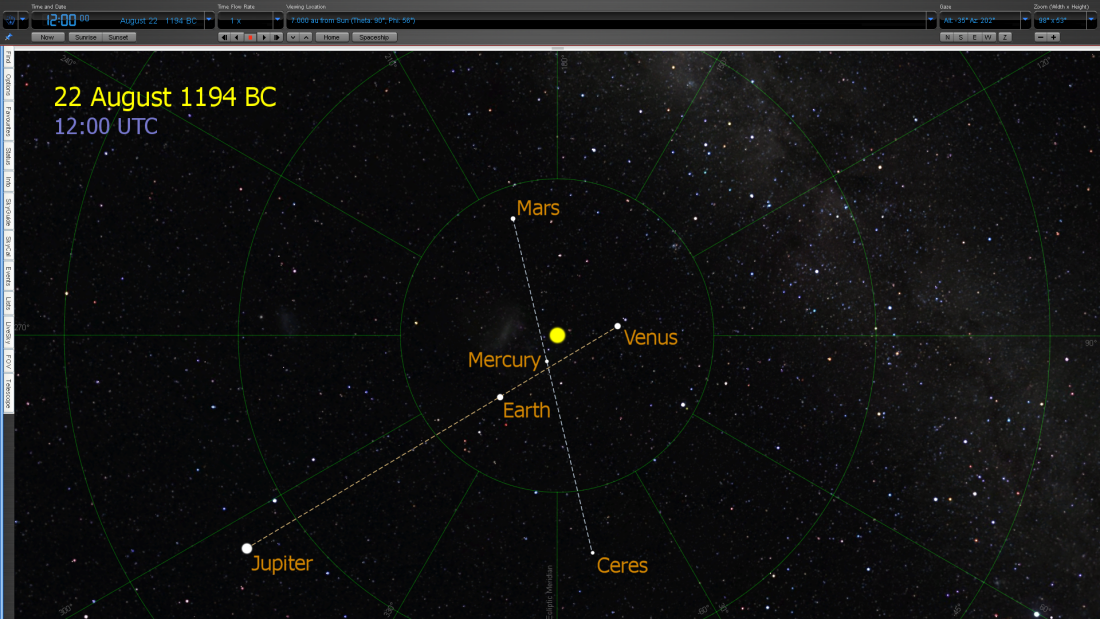

23 March 687 BC – 185000 days = 21 September 1194 BC

Does this date directly target the previously mentioned Bronze Age collapse alignment date? No. One further correction is necessary. One that is ever so ingeniously built-in to the relevant Bible passage.

To summarise the story so far, the siege of Jerusalem by Sennacherib took place whilst the sitting king of Jerusalem was Hezekiah, whose prayer to the God of the Israelites is linked to the destruction of Sennacherib’s army (of 185000 men). This is all detailed in the book of Isaiah, as previously noted. That being said however, the same story is also mentioned in another part of the Bible: 2 Kings 19.

Crucially however, in the very next section: 2 Kings 20, we follow the story after the siege is over, with King Hezekiah then becoming sick to the point of death. What leads to a further prayer to the God of Israel: that he be healed. A prayer that would appear to have been answered, with the prophet Isaiah imparting the outcome, as follows:

8 Hezekiah had asked Isaiah, “What will be the sign that the Lord will heal me and that I will go up to the temple of the Lord on the third day from now?”

9 Isaiah answered, “This is the Lord’s sign to you that the Lord will do what he has promised: Shall the shadow go forward ten steps, or shall it go back ten steps?”

10 “It is a simple matter for the shadow to go forward ten steps,” said Hezekiah. “Rather, have it go back ten steps.”

11 Then the prophet Isaiah called on the Lord, and the Lord made the shadow go back the ten steps it had gone down on the stairway of Ahaz.

2 Kings 20

Here one can see two critical items highlighted in bold: ‘third day’ and ‘ten steps,’ specifically with reference to ‘going backwards.’ Here is where the discerning reader needs insight. The clever author wants the reader to multiply three days by the number 10, which produces a total of 30 days.

This is the final correction measure which must be added to the aforementioned 185000 figure, in order to go backwards in time to the exact date of interest. The complete mathematics is therefore as follows:

23 March 687 BC – 185000 days

= 21 September 1194 BC

– 30 days

= 22 August 1194 BC - Bronze Age collapse alignment:

The above finding has many implications, well beyond offering just another proof of the decisive date for the Bronze Age collapse, as triggered by a celestial alignment. And here the reader is free to contemplate these matters further of their own accord.

Back to: Signs of the Times Menu

Notes:

[1] Concerning modelling the dwarf planet Ceres, I use Starry Night Pro 6.0 softwareSee this article for more information: Ceres Orbital Solution Considerations [2] See the 11:00 mark in this presentation: Velikovsky Lecture